not afraid of our own depths

Sermon 3-13-16

John 12:1-8

Peace Covenant CoB

Our scripture this morning is one of the strangest passages in the lead-up to Jesus’ trial, crucifixion and resurrection. I mean, almost everything that involved Jesus’s story is strange, but this one in particular is excessively, effusively strange.

We find ourselves in the home of the siblings Mary, Martha and Lazarus, at Bethany. These were Jesus’ friends – we don’t hear a lot about the inner workings of Jesus’ personal relationships in the gospels, which has led to all sorts of myth and fable about who he was or was not romantically involved with, random false “discoveries” of fragments of papyrus with weird mentions of Jesus’ “wife” kicking off a media spiral and hysteria among Christian traditionalists. We know about his family – his mother and father and that he had brothers – and we know about his colleagues – his disciples who tried and failed and tried again to live up to his high expectations, those followers he eventually relented to call “friends,” – but we don’t hear very much about Jesus’ community, Jesus’ people, Jesus’ soulmates.

Except for Lazarus, Martha and Mary. These were Jesus’ people. They offered him respite in their home during all those years he spent as an itinerant preacher. Jesus returns again and again to their home at Bethany – for rest, for respite, to soak in the love of these people who knew him the best.

And even of these three friends, we know very little. We know the story of Mary and Martha competing in the ways they love their friend – practical or emotional, Mary fixing giant feasts for Jesus and those gathered to listen to him, Martha tucking her legs underneath her as she knelt, conspicuously at his side, joining in on the theological discussions and claiming her place, even as a woman, in his world.

And we know that when Lazarus got sick and succumbed to the illness, Jesus waited two days after he got the news to come running. We know that Jesus loved this friend so much that when he did arrive – after Lazarus had died – and saw the household of his friends in such disarray and grief, Lazarus laid out as the women prepared him for burial with oils and cloths, anointing his hands and his feet even through their tears, Jesus himself sat down and wept before raising Lazarus back to life.

These relationships were deep ones, soul-friendships, friendships of both shared interests and activities but also friendships borne of spiritual connection. Mary and Martha and Lazarus KNEW Jesus. They didn’t just follow him, they didn’t just gossip about him from afar. They weren’t his constituents or his admirers, not his disciples and not his family. They were his friends, the people with whom he found refuge and the ones who loved him the most intimately.

So, when this passage opens with Jesus in the home of Mary, Martha and Lazarus, we know that he is in a place of refuge, in a place where he is loved and cared for, in a place where the people with whom he seeks and finds comfort and care are all gathered. The family gives a dinner for Jesus and his disciples, who are there with him. Martha served – because, of course, she is Martha. Lazarus was there, too, so recently the recipient of the kind of new life Jesus has been preaching and will soon embody in his own limbs and organs. And Mary, who we know has no trouble doing what she feels called to do, breaking convention for the sake of love and loyalty, goes back into the closets of the house and digs out one of the leftover jars of anointing oil that they had used when Lazarus died, one of great expense that the family had decided to save for the next ritual of grief and loss, and comes back into the room.

In scripture, people use oil for a bunch of reasons. Oil was a common tool, a household good. It was used in lamps, and on skin. People bathed with water less frequently but rubbed oil on their skin more often. Oil was the tool and symbol of leadership, too – kings get oil poured over their heads at their coronation, a sign of their riches and power. And oils were used at death, to prepare the bodies for burial.

It would seem that Mary has had, during this dinner, a premonition. She knows Jesus very well, and something about the conversation or the tension in the room that night has convinced her that he is about to face some very, very dangerous days. Something has convinced Mary that her dear friend is himself about to die. And when people die, you spare no expense in preparing them for burial. You bring out the deeply scented oils and anoint their lifeless body, you breathe in the scent of death and pair it with the scent of holy, healing, life-giving oil. Death is no time to be stingy with the resources. In grief, all the barriers come down. No expense is spared. No holds barred. If you can’t use it now, when can you?

So, Mary walks back to the dining room and kneels, once again, at Jesus’ feet. She empties the entire jar of costly nard over them – not on his head, not to mark him as a king, but on his dusty, dirty feet – and then she lets down her hair, a scandalous act for a respectable woman, and uses it to rub the oil in.

This is not an act of madness, though the entire room is scandalized by what she has done. This is an act of extravagant, intimate love. This is the no holds barred love of one of Jesus’ closest friends, the deep care of a woman who knew who he was, what he was doing, and what terror lie just ahead for him. Jesus loved his friends in this way: deeply, intimately, to the end and then some, and his friends loved him back.

Imagine being in that room that night. Imagine you were a disciple – someone who has followed Jesus and been close with him but also held him in some form of awe – at arm’s length. You would never attempt to show your respect for Jesus in such an intimate way, though he is the very best and smartest and most world-shaking person you have ever met, even though he has called you into this ridiculous adventure and convinced you that all he says – all the talk about a new world and God’s kingdom and upside-down justice – is true. Still, there’s a distance between you and him. You might feel the urge to anoint his feet with oil, but never would you act on it – too disrespectful, too weird, too undignified. You have to remain respectable, even in these strange times.

And imagine what you’d feel, as a disciple, watching Jesus’ friend Mary come out with the jar of oil, kneel down and empty it, shaking it upside down to get out even the last clinging drops; let down her hair and begin wiping his feet with it. Imagine how you’d feel – awkward? Weirded out? Worried about what other people will say when they find out just what’s been going on in that house where Jesus spends so much time? Ashamed that you couldn’t find the guts to love Jesus in the way that this woman seems to do so easily?

Judas, who was in that position, cannot take the awkward. He knows a little more than the other disciples, maybe, has just a bit more to feel guilty about. Maybe he’s already talked with the Romans, already begun to conspire against Jesus. Whatever is going on inside him, Judas is the one to speak up. He makes no mention of the foot-anointing or the hair-cloth, chooses to ignore these signs of intimacy and deep love that are making him and the rest of the room uncomfortable, and chooses, instead, to carp on the money.

OH, you guys. How easy is it to mask our feelings of awkwardness or insufficiency or shame with money talk? How many of us have deflected an unwanted emotion by picking on the economics involved? I KNOW that defense mechanism. It is easy to talk relative economic merits, and hard to admit that we have emotional issues with the situation at hand.

Judas drives straight to the heart of the money deflection: THAT OIL COULD HAVE FED A FAMILY FOR A YEAR! By which he really meant to say “HOW DARE YOU LOVE JESUS BETTER THAN I CAN?! HOW DARE YOU EXPOSE MY TREASON AND MAKE ME FACE UP TO MY OWN SINFULNESS AND BETRAYAL?!”

And Jesus, who knows everything swirling in each of their hearts, says “Leave her alone. She knows what she is doing. You know you wouldn’t sell that oil and give it to the poor, Judas, but there will come a day when you’ll have the choice to act with integrity – that choice will always be before you. For now, you get this chance to love me. And Mary is choosing the right way. She is acting with integrity right now.”

Mary loved Jesus deeply. She was one of his closest friends, and she knew who and what he was. And in this moment, her actions lined up perfectly with her emotions. She felt love, and acted on it. She didn’t deflect that scary sense of intimacy by locking herself away in the kitchen, she didn’t try to pick a fight about theology or money, she didn’t make an excuse to leave the room in order to escape her own feelings. She felt deep love, and moved to act on it. That is integrity. And Jesus commends her for it.

I wonder, then, how often we choose to ignore or disrespect or deflect our own deep emotions. I wonder how many times a day we feel something deeply and choose – instead of feeling it – to ignore it and distract ourselves. I wonder if that isn’t the point of this passage: that we are created with the ability to FEEL, deeply and that we are called to acknowledge those feelings and, occasionally, to ACT on them.

Mary gets a bad rap in the Christian tradition. She gets made into damaged goods, a woman of loose morals, an inappropriate companion for Jesus, Lord and Savior. Her openness and richness of affection for Jesus becomes sullied as something distasteful and dangerous. I think this is one of the worst things that the Church has done – and not just for women, but for all of us. By casting Mary Magdalene as dangerous and dirty, all of us lose out on Jesus’ affirmation of deep love. By equating intimacy with only sexuality – and the wrong kind of sexuality, at that, all of use lose out on the possibilities of deep, soul-friendships. By making any act of loyalty and love suspect, all of us turn to Judas-like behaviors: defending and deflecting, knee-deep in our own shame and guilt.

I think that what Jesus is saying in this moment, when he silences Judas and affirms Mary’s strange, unconventional, boundary-busting demonstration of the depth of her love for Jesus is that none of us need be afraid of our own depths. That this abundance of relationship, love, and care is not something we need to shy away from. That celebrating relationship while it exists is the way to go.

This morning, we have the opportunity to participate in the practice of anointing. In the Church of the Brethren, we anoint one another – a simple touch with cool, fragrant oil on the forehead – for healing, for forgiveness of sin, and for strengthening of faith.

Some of us this morning may be in deep need of healing, physical or emotional or spiritual. Others of us may be in need of forgiveness. And still others may come for anointing so that our faith may be strengthened. All of those are real and valid reasons to request anointing. The oil and blessing are meant for all these things.

And. As we reflect on the story of Martha anointing Jesus’ feet, I also wonder about anointing one another for boldness and abundance – that our faith might be strengthened enough for us to love one another without fear. That we might be given the courage to speak our care for one another, to share friendship in the forms of encouragement and phone calls and casseroles and hugs, to be freed from the chains of shame and respectability and fear that hold us back. To be granted the grace to love one another just as Jesus has loved us: with such abundance and effusiveness that he knelt, just a few days later, and repeated Mary’s strange act: with water instead of oil, a towel instead of hair, but kneeling, nonetheless, at the feet of his friends, proclaiming his deep love for them.

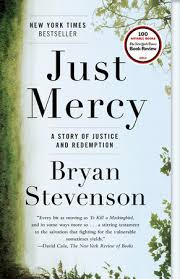

This book was recommended to me by just about every Christian radical friend I know BEFORE it appeared on every Starbucks counter in the land. That’s some serious crossover cache, I think, to be tripping off the tongues of Christian anarchists AND the biggest coffee capitalists the world over. I guess it’s a testament to how beautiful a book it is. Stevenson has been working for decades as a lawyer on behalf of those on death row, kids tried as adults, and impoverished people encountering our unjust justice system. His stories are harrowing, his writing is generous, and – though he never frontloads it – his faith is strong and shining. If you’ve been wondering where to find stories to complete the picture of Michelle Alexander’s statistics, if you’ve been hoping for some deeply invested, even-handed, mercy-for-all perspective on the American criminal and penal systems, or if you just appreciate passionate people writing compassionately and engagingly about their lives’ work, go pick it up.

This book was recommended to me by just about every Christian radical friend I know BEFORE it appeared on every Starbucks counter in the land. That’s some serious crossover cache, I think, to be tripping off the tongues of Christian anarchists AND the biggest coffee capitalists the world over. I guess it’s a testament to how beautiful a book it is. Stevenson has been working for decades as a lawyer on behalf of those on death row, kids tried as adults, and impoverished people encountering our unjust justice system. His stories are harrowing, his writing is generous, and – though he never frontloads it – his faith is strong and shining. If you’ve been wondering where to find stories to complete the picture of Michelle Alexander’s statistics, if you’ve been hoping for some deeply invested, even-handed, mercy-for-all perspective on the American criminal and penal systems, or if you just appreciate passionate people writing compassionately and engagingly about their lives’ work, go pick it up.